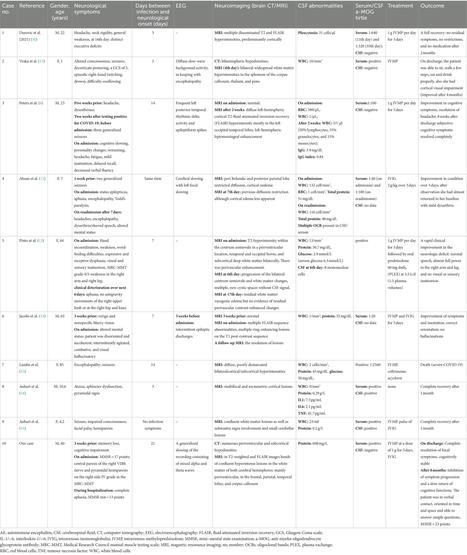

Abstract Background and Objectives To determine the real-world use of rituximab in autoimmune encephalitis (AE) and to correlate rituximab treatment with the long-term outcome. Methods Patients with NMDA receptor (NMDAR)-AE, leucine-rich glioma-inactivated-1 (LGI1)- AE, contactin-associated protein-like-2 (CASPR2)-AE, or glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65) disease from the GErman Network for Research on AuToimmune Encephalitis who had received at least 1 rituximab dose and a control cohort of non–rituximab-treated patients were analyzed retrospectively. Results Of the 358 patients, 163 (46%) received rituximab (NMDAR-AE: 57%, CASPR2-AE: 44%, LGI1-AE: 43%, and GAD65 disease: 37%). Rituximab treatment was initiated significantly earlier in NMDAR- and LGI1-AE (median: 54 and 155 days from disease onset) compared with CASPR2-AE or GAD65 disease (median: 632 and 1,209 days). Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores improved significantly in patients with NMDAR-AE, both with and without rituximab treatment. Although being more severely affected at baseline, rituximab-treated patients with NMDAR-AE more frequently reached independent living (mRS score ≤2) (94% vs 88%). In LGI1-AE, rituximab-treated and nontreated patients improved, whereas in CASPR2-AE, only rituximab-treated patients improved significantly. No improvement was observed in patients with GAD65 disease. A significant reduction of the relapse rate was observed in rituximab-treated patients (5% vs 13%). Detection of NMDAR antibodies was significantly associated with mRS score improvement. A favorable outcome was also observed with early treatment initiation. Discussion We provide real-world data on immunosuppressive treatments with a focus on rituximab treatment for patients with AE in Germany. We suggest that early and short-term rituximab therapy might be an effective and safe treatment option in most patients with NMDAR-, LGI1-, and CASPR2-AE. Class of Evidence This study provides Class IV evidence that rituximab is an effective treatment for some types of AE. Glossary abs=antibodies; AE=autoimmune encephalitis; CA=cerebellar ataxia; CASPR2=contactin-associated protein-like-2; CBA=cell-based assay; GAD65=glutamic acid decarboxylase 65; GENERATE=GErman Network for Research on AuToimmune Encephalitis; IHC=immunohistochemistry; IVIG=IV immunoglobulin; LE=limbic/autoimmune encephalitis; LGI1=leucine-rich glioma-inactivated-1; mRS=Modified Rankin Scale; NMDAR=NMDA receptor; RIA=radioimmunoassay; SPS=stiff-person syndrome Autoimmune encephalitis (AE) is an umbrella term for an emerging spectrum of immune-mediated neuropsychiatric disorders often associated with antibodies (abs) against neuronal cell surface, synaptic, or intracellular proteins.1,2 Anti-NMDA receptor (NMDAR)-AE, anti–leucine-rich glioma-inactivated-1 (LGI1)-AE, anti–contactin-associated protein-like-2 (CASPR2)-AE, and anti–glutamic acid decarboxylase-65 (GAD65) disease together make up the majority of seropositive AE subtypes. NMDAR-AE affects young adults and children with female preponderance, is frequently associated with ovarian teratomas, and causes psychiatric symptoms, movement disorders, decreased consciousness, autonomic dysregulation, epileptic seizures, and central apnea.3,4 LGI1-AE affects middle-aged or elderly patients, causes short-term memory deficits, confusion, and epileptic seizures,5,6 and is sometimes preceded by faciobrachial dystonic or tonic seizures.7 CASPR2-AE predominantly affects elderly men and causes encephalitis and neuromyotonia, neuropathic pain, ataxia, myoclonus, autonomic dysfunction, or a combination thereof (e.g., Morvan syndrome).8,9 GAD65 disease is considerably more heterogeneous, affects predominantly women of all ages, and may cause cerebellar ataxia (CA), limbic/AE (LE), stiff-person syndrome (SPS), isolated temporal lobe epilepsy, and overlap forms of the aforementioned manifestations.10,-,13 Early diagnosis and prompt initiation of immunotherapy is crucial and often leads to substantial or complete recovery from these severe disorders.8 However, treatment data from randomized trials are scarce.14,15 Empiric treatment of AE usually consists of a step-wise escalation of immunotherapy including first-line therapy with steroids, plasma exchange, IV immunoglobulin (IVIG), or combinations, followed by second-line therapy with cyclophosphamide, rituximab, or combinations.2 Rituximab is a B cell–depleting monoclonal ab directed against CD20 with established efficacy in many neurologic autoimmune diseases including MS,16 and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders.17 Rituximab was shown to be effective in AE associated with different auto-abs.4,18,19 By contrast, 1 randomized placebo-controlled trial with rituximab did not show efficacy in patients with SPS.15 Detailed and comparative evaluations of rituximab use and the long-term outcome between AE subtypes in a real-world setting are missing. In this study, we evaluated demographic and clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, and immunotherapies in patients with NMDAR-, LGI1-, CASPR2-AE, or GAD65 disease in a cohort from the GErman NEtwork for Research on AuToimmune Encephalitis (GENERATE) registry and compared patients who had received at least 1 rituximab dose with non–rituximab-treated patients. In the rituximab cohort, we specifically correlated early, high-dose, or prolonged rituximab treatment with the long-term outcome. Methods Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents All data were collected from the GENERATE registry, which is a noninterventional retrospective and prospective multicentric database for patients with AE in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (generate-net.de). GENERATE was approved by the institutional review boards of all actively recruiting centers. Patients from participating centers entered into the registry until June 30, 2019, were analyzed. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All enrolled patients or their legal representatives gave written informed consent before enrollment in the registry. Study Population The following patients were included: (1) patients with detection of NMDAR-, LGI1-, CASPR2-, or GAD65 abs according to the ab criteria below; (2) clinical diagnosis of AE based on the consensus criteria published in reference 2, or for patients with GAD abs, alternatively diagnosis of CA or SPS; (3) any documented treatment with rituximab; and (4) available information on the number, dosage, and timing of rituximab infusions. In addition, a control cohort with consistent inclusion criteria except for rituximab treatment was included. Analysis of Clinical, Laboratory, and Immunotherapy Profiles Ab testing was performed in the respective GENERATE centers using cell-based assays (CBAs) and confirmation by immunofluorescence (commercial test kit panels Euroimmun, Lübeck) and/or immunohistochemistry (IHC) for NMDAR, LGI1, and CASPR2, and ELISA, radioimmunoassay (RIA), or CBA for GAD65. Patients fulfilling the following ab criteria in earliest available samples were included: NMDAR abs detected in serum by CBA confirmed by IHC (in the absence of confirmatory IHC in serum, only CBA serum titers of >1:500 were considered specific) and/or CSF positive; GAD abs >1:500 in CBA or >2000IE/mL in ELISA or RIA in serum and/or CSF positive; LGI1 abs at any titer in CSF and/or serum; CASPR2 abs >1:128 in serum and/or CSF positive.20 Only IgG abs were considered relevant. Data on any immunotherapy were recorded. First-line immunotherapy was defined as treatment with corticosteroids, plasma exchange/immunoabsorption, and IVIG; second-line therapy included rituximab in the rituximab cohort and all other immunotherapies except reapplied corticosteroids, IVIG, and plasma exchange in both cohorts. The occurrence of relapses during follow-up was based on the overall clinical impression of the treating physician. Functional status was assessed using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at the peak of disease and then throughout disease course. Side effects of rituximab treatment were queried from all participating centers. Primary Research Question Do rituximab-treated patients with NMDAR-AE, LGI1-AE, CASPR2-AE, and GAD65 disease have a better outcome than non–rituximab-treated patients? Classification of Evidence This study provides Class IV evidence that rituximab is an effective treatment for some types of AE. Statistics Statistical tests were performed using Prism Software (GraphPad). Normality testing was performed using the D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus test. Continuous variables with >2 subgroups were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn multiple comparisons test and with 2 subgroups using the Mann-Whitney test. Ordinal variables were compared using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was performed to control for multiple testing. Multivariate analysis was performed by ordinal logistic fit using JMP software (Version 16, JMP, A Business Unit of SAS, Cary, NC). Data Availability No deidentified patient data will be shared. No study-related documents will be shared. Reasonable requests from any qualified investigator for anonymized data will be considered by the corresponding author. Results Patient Characteristics We identified 358 patients with NMDAR-AE, GAD65 disease, LGI1-AE, or CASPR2-AE. One hundred sixty-three patients (46%) were treated with rituximab. Based on the inclusion criteria, 14 patients in the rituximab cohort and 32 patients in the control cohort were excluded from further analysis (Figure 1, eFigure 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A595). Our final study cohort comprised 149 patients in the rituximab cohort (NMDAR-AE: n = 81, GAD65 disease: n = 31, LGI1-AE: n = 26, and CASPR2-AE: n = 11) and 163 patients in the control cohort (NMDAR-AE: n = 61, GAD65 disease: n = 53, LGI1-AE: n = 35, and CASPR2-AE: n = 14) (Figure 1). Overall, rituximab was administered most frequently in NMDAR-AE (57%), followed by CASPR2-AE (44%), LG1-1-AE (43%), and GAD65 disease (37%). Clinical characteristics as well as CSF and MRI parameters, as expected, varied considerably between the ab subgroups (Table 1). Differences between the rituximab cohort and the control cohort indicating severity bias were observed for patients with NMDAR-AE and GAD65 disease: patients with NMDAR-AE treated with rituximab had a significantly higher mRS score at peak of disease (rituximab cohort: median: 4.0; control cohort: median: 3.0) and a significantly higher frequency of decreased consciousness (Table 1). In patients with GAD65 disease, the mRS score at the peak of disease was also higher in the rituximab cohort (median: 3.0) compared with the control cohort (median: 2.0) (Table 1). Figure 1 Study Population Profile Patient numbers in the different study subpopulations are depicted. *Patients excluded because of insufficient data on rituximab dosing (n = 2), concomitant diagnosis of MS (n = 2), retraction of consent for the GENERATE registry (n = 1), or not fulfilling the ab criteria for inclusion (n = 9). **Patients excluded because of insufficient data on immunosuppressive treatment (n = 1) or not fulfilling the ab criteria for inclusion (n = 31). CA, cerebellar ataxia; CASPR2 = contactin-associated protein-like-2; Enc. = encephalitis; GAD65 = glutamic acid decarboxylase 65; GENERATE = GErman Network for Research on AuToimmune Encephalitis; LGI1 = leucine-rich glioma-inactivated-1; NMDAR = NMDA receptor; SPS = stiff-person syndrome. View inline View popup Table 1 Characterization of the Patient Cohort First-Line and Second-Line Treatments All patients with rituximab treatment received prior first-line immunotherapy. In the control cohort, 4 patients (7%) with NMDAR-AE, 5 patients (9%) with GAD65 disease, and 1 patient (7%) with CASPR2-AE had no prior first-line immunotherapy (Table 2). Time to initiation of first-line therapy was shortest in patients with NMDAR-AE, and the therapy was started significantly earlier in patients with NMDAR-AE treated with rituximab (median: 16 days) compared with patients with NMDAR-AE not receiving rituximab (median: 33 days) (Table 2). In all subgroups, the majority of patients received a combination of different first-line treatments with steroids and plasma exchange being the most frequent combination in the overall cohort (n = 103; 33%) (Figure 2, A–H). As expected, because of severity bias, patients in the rituximab cohort were treated significantly more often with combinations of first-line therapy (Figure 2, A–H). Physicians reported some improvement following first-line therapy in the majority of patients independent of the subgroup. Of interest, the frequency of this observation was similar between patients later receiving rituximab and patients who were treated differently (Table 2). View inline View popup Table 2 Immunotherapy and Follow-up of Patients Figure 2 Venn/Euler Diagrams Showing Applied Mono- and Combination First-Line and Second-Line Immunotherapies The numbers of patients treated with the respective prior first-line immunotherapies (A–H) and second-line immunotherapies (I–P) in the rituximab cohort (A–D) and in the control cohort (E–H) are depicted for the different ab subgroups (A, E, I, and M: NMDAR-AE; B, F, J, and N: GAD65 disease; C, G, K, and O: LGI1-AE; and D, H, L, and P: CASPR2-AE). Other second-line therapies included bortezomib (n = 6 in patients with NMDAR-AE treated with rituximab), daratumumab (n = 1 in patients with NMDAR-AE treated with rituximab), tacrolimus (n = 1 in patients with GAD65 disease treated with rituximab and n = 1 in patients with GAD65 disease not treated with rituximab), and basiliximab (n = 1 in patients with GAD65 disease treated with rituximab). Areas of Venn diagrams are proportional to the case numbers relative to the respective subgroup. (A–H) Proportions of combination first-line therapy relative to none/monotherapy were compared using the Fisher exact test. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05. (I–P) Proportions of treatment with cyclophosphamide or other therapies relative to steroid-sparing therapies and no treatment were compared using the Fisher exact test. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05. AZA = azathioprine; CASPR2 = contactin-associated protein-like-2; cyc = cyclophosphamide; GAD65 = glutamic acid decarboxylase 65; IVIG = IV immunoglobulin; MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; MTX = methotrexate; NMDAR = NMDA receptor; LGI1 = leucine-rich glioma-inactivated-1; PLEX = plasma exchange. Forty patients (25%) in the control cohort and 38 patients (26%) in the rituximab cohort received a second-line immunotherapy other than rituximab. The frequency of application of second-line immunotherapies other than rituximab did not differ between the rituximab cohort and the control cohort (Table 2). These second-line immunotherapies included cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, bortezomib, daratumumab, tacrolimus, and basiliximab (Figure 2, I–P) and were applied before, parallel to, or after rituximab therapy. In patients with NMDAR-AE and GAD65 disease, more aggressive second-line therapies such as cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, or daratumumab were applied more frequently in the rituximab cohort compared with the control cohort (Figure 2, I–P). Other than this and the above-mentioned severity bias, we did not observe significant selection bias between patients treated with and without rituximab. Description of Rituximab Treatments A wide spectrum of rituximab treatment regimens was observed in our rituximab cohort. In detail, patients with GAD65 disease and CASPR2-AE received rituximab significantly later (GAD65: median 1,209 days, CASPR2: 632 days) than patients with NMDAR-AE (median: 54 days) and LGI1-AE (median: 155 days) (Figure 3A; Table 2). Time from initiation of first-line treatment to rituximab treatment was shortest in NMDAR-AE (median: 30 days) and longest in GAD65 disease (median: 141 days) (Figure 3B; Table 2). Sixteen (20%) patients with NMDAR-AE received rituximab very early within 2 weeks after first-line immunotherapy. The median number of infusions and total rituximab dose did not differ significantly among the subgroups (Figure 3C, D; Table 2). The duration of rituximab treatment, defined as the time from first to last infusion, was shortest in NMDAR-AE (median: 24 days) and longest in GAD65 disease (median: 454 days) (Figure 3E and Table 2). The percentage of patients who received only induction therapy defined as time between first to last rituximab treatment of less than 6 months was highest in patients with NMDAR-AE (54%) and lowest in patients with GAD65 abs (27%); patients with LGI1- and CASPR2-AE were in between (35% and 46%, respectively) (Figure 3F; Table 2). Side effects after rituximab treatment were rare (n = 5, 3.4%); however, they were not systematically registered in this study. In detail, we observed n = 2 infusion-related reactions (n = 1: urticaria with, however, simultaneous IVIG application; n = 1: tremor, tachycardia, and fear); n = 1 lymphopenia leading to a reduction of the rituximab dose; n = 1 frequent infections; and n = 1 unknown side effect. Figure 3 Rituximab Regimens Used in Patients With AE and the Outcome According to Subtypes of AE (A–F) In different subgroups (NMDAR-AE, GAD65 disease, LGI1-AE, and CASPR2-AE), the duration in days from disease onset to initiation of rituximab treatment (A), the duration in days from initiation of first-line therapy to initiation of rituximab treatment (B), the number of rituximab infusions (C), the total cumulative rituximab dose (D), the duration in days from the first to the last rituximab infusion (E), and the number of patients receiving induction therapy (rituximab treatment <6 months) or induction + maintenance therapy (rituximab treatment ≥6 months) (F) are depicted. Bars indicate the median. Normality testing was performed using the D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus test. Continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn multiple comparisons test, and ordinal variables were compared using the Fisher exact test. ****p<0.0001 ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05. (G) mRS scores in the different ab subgroups were compared in the rituximab cohort and in the control cohort. The distribution of mRS scores is depicted at 4 time points: I, maximal mRS at symptom onset; II, mRS at initiation of rituximab treatment (from −2 months to +4 months from rituximab onset); III, mRS 4–12 months after initiation of rituximab treatment; IV, mRS at last follow-up with at least >12 months after rituximab treatment. The line represents the change in mRS scores dividing favorable mRS scores (0–2) and nonfavorable mRS scores (≥3). The ordinal χ2 test was applied to compare the distribution of mRS scores. ****p<0.0001 ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05. CASPR2, contactin-associated protein-like-2; GAD65 = glutamic acid decarboxylase 65; mRS = modified Rankin Scale; NMDAR = NMDA receptor; LGI1 = leucine-rich glioma-inactivated-1. Follow-up and Treatment Response Follow-up data were available for 282 patients (90%) with a median follow-up duration of 41 months with no significant differences between rituximab-treated patients and controls regarding follow-up data availability and duration (Table 2). The distribution of mRS scores at the peak of disease and at last follow-up improved significantly in patients with NMDAR-AE and in patients with LGI1-AE both in the rituximab cohort and in the control cohort. In patients with CASPR2-AE, a significant improvement was observed only in the rituximab cohort, but not in the control cohort. No significant improvement was observed in patients with GAD65 disease (Figure 3G). In addition, in patients with GAD65 disease, no significant improvement was observed when mRS scores were analyzed in the different disease subentities (encephalitis/overlap syndrome, CA, and SPS) (eFigure 2A, links.lww.com/NXI/A596). Although patients with NMDAR-AE treated with rituximab were affected more severely at baseline (Table 1), at final follow-up, 94% of rituximab-treated patients compared with 88% of nontreated patients had reached independent living (mRS score ≤2, p = 0.33). Patients with LGI1-AE reached independent living in 83% of cases treated with rituximab and in 78% of cases without rituximab treatment (p = 0.74). In CASPR2-AE, independent living was observed in 80% of cases treated with rituximab vs 57% of cases who did not receive B-cell depletion (p = 0.60). In contrast, patients with GAD65 disease treated with rituximab, who were more severely affected at baseline, continued to have a lower rate of independent living compared with the non–rituximab-treated control cohort at last follow-up (52% vs 75%, p = 0.07). When we analyzed the mRS scores in the rituximab cohort throughout follow-up in more detail, we found patients with NMDAR-AE to improve significantly already before rituximab initiation (Figure 3, G.a I-II), presumably because of first-line treatments. After initiation of rituximab treatment, patients continued to improve significantly (Figure 3G.a II-III). No significant difference in the mRS score was observed in patients with NMDAR-AE exhibiting a tumor compared with those without a tumor both regarding mRS score at worst status and mRS score at last follow-up (eFigure 2B, links.lww.com/NXI/A596). In LGI1 patients, a significant improvement was also already observed before rituximab treatment was initiated (Figure 3G.c I-II). After initiation of rituximab treatment, the mRS scores continued to drop; however, this improvement did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3G.c II-IV). In patients with CASPR2-AE, mRS scores decreased after initiation of rituximab treatment (Figure 3G.d II-IV) without reaching significance presumably because of small patient numbers. Nineteen relapses (14%) were reported during follow-up in the rituximab cohort (NMDAR-AE: n = 13, 19%; LGI1-AE: n = 5, 20%; and CASPR2-AE: n = 1, 11%). Of note, only 6 relapses (5%) in the rituximab cohort occurred after rituximab treatment was started (NDMAR-AE: n = 3, 4%; LGI1-AE: n = 3; 12%) (Table 2). The other 13 relapses occurred before rituximab initiation. In the control cohort, 19 relapses (13%) occurred (NMDAR-AE: n = 7, 13%; LGI1-AE: n = 10, 31%; CASPR2-AE: n = 2, 14%), which was more frequent than those observed in the rituximab group after initiation of rituximab (p = 0.02) (Table 2). Finally, we performed a multivariate analysis for the rituximab cohort to identify factors associated with the extent of improvement as measured by the change in the mRS score from baseline to last follow-up. Most significantly, the AE subtype (NMDAR-AE) was associated with mRS score improvement, whereas rituximab dosage and duration were not significantly associated with an improved mRS score (Table 3). MRS score improvement was also observed for early initiation of rituximab treatment (≤60 days after initiation of first-line treatment), and a trend was observed for early initiation of first-line treatment (≤30 days after symptom onset). View inline View popup Table 3 Multivariate Analysis of the Outcome Discussion This study describes real-world data on rituximab usage in a large German cohort of patients with the most common AE subtypes. We confirm the following: (1) Rituximab is the most frequent second-line immunotherapy that is used in nearly half of all patients with AE in Germany. (2) Rituximab usage differs within AE subtypes with patients with NMDAR-AE most frequently and patients with GAD65 disease least frequently receiving rituximab. Treatment was in all cases initiated following prior first-line immunotherapy. Patients with NMDAR-AE and GAD65 disease were more likely to be treated with rituximab if they presented with more severe disease (decreased levels of consciousness and higher mRS). (3) Patients with NMDAR-AE were treated earlier and more often (54%) received a short-term rituximab treatment (<6 months) without repeated maintenance reinfusion than other AE subgroups. (4) The long-term outcome in patients with NMDAR-, LGI1-, and CASPR2-AE in the overall cohort was favorable with 91%, 80%, and 63% of the patients being able to function independently at last follow-up, respectively. (5) Although comparison of patients with and without rituximab treatment is prone to severity bias, we found some hints of a better outcome and fewer relapses in the former group: patients with NMDAR-AE treated with rituximab more often reached independent living at last follow-up although being affected more severely at baseline; patients with CASPR2-AE improved significantly better under rituximab treatment; patients with NMDAR-E and LGI1-AE experienced fewer relapses if treated with rituximab. (6) No significant improvement during follow-up of patients with GAD65 disease was observed both in the rituximab cohort and in the control cohort. However, although we did not observe a group effect in GAD65 disease, some individuals showed a remarkable response associated with B cell–depleting treatment. In NMDAR-AE, treatment with rituximab is widely accepted. It has been used empirically since the first description of NMDAR-AE, and a large prospective case series4 and a systematic review21 could add further evidence that early second-line immunotherapy in patients not responding sufficiently to first-line immunotherapy was associated with better outcomes and fewer relapses. Recently, a meta-analysis of 14 retrospective and prospective case series summarizing 277 patients with AE (88.8% NMDAR-AE) concluded that rituximab is an effective second-line agent with an acceptable toxicity profile.19 Our data confirm and extend these observations. We found patients with NMDAR-AE treated with rituximab to have a favorable outcome. As patients treated with induction or maintenance therapy did not significantly differ in the outcome, our data support the notion that in many patients with NMDAR-AE, short-term rituximab treatment might be sufficient to control the disease. In a recent position paper by the Autoimmune Encephalitis Alliance Clinicians Network,22 this is reflected by the recommendation to consider long-term rituximab treatment mainly in relapsing disease. Compared with NMDAR-AE, considerably less information on long-term immunosuppression and especially rituximab is available in other AE subtypes. For LGI1-AE, early initiation of any immune therapy was associated with better outcomes in studies with 297 and 13 patients,23 respectively. Only few patients were treated with rituximab in retrospective case series19,24,25 and a small open-label trial.26 In our cohort, we observed a surprisingly favorable outcome in patients with LGI1-AE, with 80% reaching independent living (mRS score ≤2) (83% in the rituximab cohort and 78% in the control cohort). A systematic review21 showed full recovery or an mRS score of 0 in 27.8% of patients, with 8% of patients treated with rituximab and 18% of patients receiving second-line treatment. In light of these findings, we believe that rituximab treatment can be considered early in patients with LGI1-AE as 1 possible immunosuppressive treatment, although the duration of therapy is unclear. Relapses occurred in 16% of patients with NMDAR-AE and 26% with LGI1-AE in our overall cohort. Previously, relapses were reported in 11.2% (85/758) of patients with NMDAR-AE and 18.8% (16/85) with LGI1-AE.21 However, we did observe a reduced rate of relapses in patients with NMDAR-AE and LGI1-AE treated with rituximab compared with patients without (independent of other second-line immunotherapies) suggesting better efficacy of rituximab in preventing relapses compared with other regimens. Nevertheless, this should be interpreted with caution because absolute patient numbers are small and controlled studies missing. For the treatment of CASPR2-AE, even less evidence exists. In our series, 44% of patients with CASPR2-AE (n = 11) were treated with rituximab albeit considerably later than patients with NMDAR-AE. We could show significant improvement in patients with CASPR2-AE treated with rituximab, which was not observed in the control group. Although patient numbers were small, our results suggest an effect of rituximab treatment in CASPR2-AE but also indicate the need for larger numbers. Immunotherapeutic strategies for GAD65-AE remain highly controversial.27 Most patients are considered to require immunotherapy, and early immunotherapy has been found to be associated with a better outcome.10,28 However, the different neurologic manifestations of SPS, CA, and LE appear to respond differently to treatments.27 Treatment of SPS with IVIG has been examined in a small crossover placebo-controlled trial in 16 patients with SPS11 and showed efficacy in approximately 80% of patients. The use of plasma exchange and corticosteroids was linked to ambiguous clinical responses,29,30 and immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and mycophenolate mofetil are currently used in clinical practice, however, with insufficient evidence from larger clinical trials.30,31 Rituximab was examined in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 24 patients with GAD65-SPS yet surprisingly did not show significant effects, possibly because of the long disease duration at the time of treatment initiation (8.0 years).15 The long-term outcome in SPS in general was poor, with 40% of patients not responding to immunotherapy.32 Although small case series show a benefit from immunotherapy including rituximab in GAD65-CA in 41%–48% of cases,33,34 the long-term outcome is poor in approximately 65% of patients.10 Similarly, most patients with GAD65-LE continue to have seizures with or without immunotherapy.35,36 Our data are in line with these observations. Rituximab treatment was initiated very late after onset of symptoms in our patients, and we did not find a significant association with a better outcome in these patients. Yet, the functional level was better than expected with 67% of patients being able to live independently (mRS score ≤2) (52% in the rituximab group and 75% in the control group). In summary, our data support the notion that long-standing GAD65 disease does not respond to rituximab therapy. However, patients in early disease stages might be more likely to respond to rituximab treatment; however, response is difficult to predict, and a lack of response should trigger benefit-risk reevaluation of rituximab therapy. We analyzed data acquired by the GENERATE network, a multicenter registry for AE in Germany. Of note, all participating centers had experience in treatment of AE, and thus, our study is not necessarily representative for nonexpert centers or centers outside Germany. Further limitations of our study are the observational character going along with a severity bias when patients with and without rituximab treatment are compared and the difficulty to differentiate rituximab treatment effects from spontaneous improvements or improvements due to concomitant treatments, the incomplete follow-up data with potential selection bias, and the lack of clinical criteria defining response to first-line therapies. Nevertheless, because randomized trials are difficult to conduct in rare diseases such as AE, real-world data from registries add important information on treatment profiles and sequences and may lead to standardized treatment protocols. In addition, single-center bias is unlikely due to the multicenter approach. Analysis of auto-ab levels, B-cell counts, and biomarkers like serum neurofilament light chain concentration throughout treatment course could add to future studies investigating the response to rituximab treatment in AE. In addition, safety data should be captured systematically. Our results support the efficacy of early rituximab treatment in NMDAR-, LGI1-, and CASPR2-AE and suggest that short-term therapy could be a treatment option. They also suggest that patients with long-standing GAD65 disease are less likely to benefit from B-cell depletion than the other AE subgroups. Nevertheless, future controlled, randomized, and prospective studies in addition to national and supranational registries with collaborative research efforts are in dire need in the field of AE. As an example of such collaborative research, the multicentric, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled phase II study GENERATE-BOOST is currently investigating the response to bortezomib in patients with severe AE. Study Funding This work was supported by the Else Kröner Fresenius Stiftung (2011_A154), the Gemeinnützige Hertie Stiftung, the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (CONNECT-GENERATE, 01GM1908), and the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology (SyNergy). Disclosure The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures. Acknowledgment The authors thank the patients and relatives contributing by donating their pseudonymized data and biomaterials to the GENERATE network. Appendix 1 Authors Appendix 2 Coinvestigators Footnotes Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures. Funding information is provided at the end of the article. F. Leypoldt and T. Kümpfel contributed equally to this work as co–senior authors. German Network for Research on Autoimmune Encephalitis (GENERATE) coinvestigators are listed in Appendix 2 at the end of the article. The Article Processing Charge was funded by the authors. Class of Evidence: NPub.org/coe Received February 12, 2021. Accepted in final form August 23, 2021. Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the American Academy of Neurology. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND), which permits downloading and sharing the work provided it is properly cited. The work cannot be changed in any way or used commercially without permission from the journal. References 1.↵Leypoldt F, Armangue T, Dalmau J. Autoimmune encephalopathies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1338(1):94-114.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 2.↵Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):391-404.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 3.↵Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, et al. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(12):1091-1098.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 4.↵Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):157-165.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 5.↵Irani SR, Alexander S, Waters P, et al. Antibodies to Kv1 potassium channel-complex proteins leucine-rich, glioma inactivated 1 protein and contactin-associated protein-2 in limbic encephalitis, Morvan's syndrome and acquired neuromyotonia. Brain. 2010;133(9):2734-2748.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 6.↵Lai M, Huijbers MG, Lancaster E, et al. Investigation of LGI1 as the antigen in limbic encephalitis previously attributed to potassium channels: a case series. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(8):776-785.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 7.↵Irani SR, Michell AW, Lang B, et al. Faciobrachial dystonic seizures precede Lgi1 antibody limbic encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(5):892-900.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 8.↵Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Dalmau J. Encephalitis and antibodies to synaptic and neuronal cell surface proteins. Neurology. 2011;77(2):179-189.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 9.↵Irani SR, Pettingill P, Kleopa KA, et al. Morvan syndrome: clinical and serological observations in 29 cases. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(2):241-255.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 10.↵Arino H, Gresa-Arribas N, Blanco Y, et al. Cerebellar ataxia and glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies: immunologic profile and long-term effect of immunotherapy. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(8):1009-1016.OpenUrl 11.↵Dalakas MC, Li M, Fujii M, Jacobowitz DM. Stiff person syndrome: quantification, specificity, and intrathecal synthesis of GAD65 antibodies. Neurology. 2001;57(5):780-784.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 12.↵Giometto B, Miotto D, Faresin F, Argentiero V, Scaravilli T, Tavolato B. Anti-gabaergic neuron autoantibodies in a patient with stiff-man syndrome and ataxia. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143(1−2):57-59.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 13.↵Gresa-Arribas N, Arino H, Martinez-Hernandez E, et al. Antibodies to inhibitory synaptic proteins in neurological syndromes associated with glutamic acid decarboxylase autoimmunity. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121364.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 14.↵Dubey D, Britton J, McKeon A, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune LGI1/CASPR2 epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2020;87(2):313-323.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 15.↵Dalakas MC, Rakocevic G, Dambrosia JM, Alexopoulos H, McElroy B. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of rituximab in patients with stiff person syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2017;82(2):271-277.OpenUrl 16.↵Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):676-688.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 17.↵Trebst C, Jarius S, Berthele A, et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica: recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). J Neurol. 2014;261(1):1-16.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 18.↵Lee WJ, Lee ST, Byun JI, et al. Rituximab treatment for autoimmune limbic encephalitis in an institutional cohort. Neurology. 2016;86(18):1683-1691.OpenUrl 19.↵Nepal G, Shing YK, Yadav JK, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in autoimmune encephalitis: a meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020;142(5):449-459.OpenUrl 20.↵Bien CG, Bien CI, Dogan Onugoren M, et al. Routine diagnostics for neural antibodies, clinical correlates, treatment and functional outcome. J Neurol. 2020;267(7):2101-2114.OpenUrl 21.↵Nosadini M, Mohammad SS, Ramanathan S, Brilot F, Dale RC. Immune therapy in autoimmune encephalitis: a systematic review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15(12):1391-1419.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 22.↵Abboud H, Probasco J, Irani SR, et al. Autoimmune encephalitis: proposed recommendations for symptomatic and long-term management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;15(12):1391-1419.OpenUrl 23.↵Shin YW, Lee ST, Shin JW, et al. VGKC-complex/LGI1-antibody encephalitis: clinical manifestations and response to immunotherapy. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;265(1-2):75-81.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 24.↵Arino H, Armangue T, Petit-Pedrol M, et al. Anti-LGI1-associated cognitive impairment: Presentation and long-term outcome. Neurology. 2016;87(8):759-765.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 25.↵van Sonderen A, Thijs RD, Coenders EC, et al. Anti-LGI1 encephalitis: clinical syndrome and long-term follow-up. Neurology. 2016;87(14):1449-1456.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 26.↵Irani SR, Gelfand JM, Bettcher BM, Singhal NS, Geschwind MD. Effect of rituximab in patients with leucine-rich, glioma-inactivated 1 antibody-associated encephalopathy. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(7):896-900.OpenUrl 27.↵Graus F, Saiz A, Dalmau J. GAD antibodies in neurological disorders - insights and challenges. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(7):353-365.OpenUrlPubMed 28.↵Di Giacomo R, Deleo F, Pastori C, et al. Predictive value of high titer of GAD65 antibodies in a case of limbic encephalitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2019;337:577063.OpenUrl 29.↵Vasconcelos OM, Dalakas MC. Stiff-person syndrome. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2003;5(1):79-90.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 30.↵Tsiortou P, Alexopoulos H, Dalakas MC. GAD antibody-spectrum disorders: progress in clinical phenotypes, immunopathogenesis and therapeutic interventions. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14:17562864211003486.OpenUrl 31.↵Hao W, Davis C, Hirsch IB, et al. Plasmapheresis and immunosuppression in stiff-man syndrome with type 1 diabetes: a 2-year study. J Neurol. 1999;246(8):731-735.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 32.↵McKeon A, Robinson MT, McEvoy KM, et al. Stiff-man syndrome and variants: clinical course, treatments, and outcomes. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(2):230-238.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 33.↵Mitoma H, Hadjivassiliou M, Honnorat J. Guidelines for treatment of immune-mediated cerebellar ataxias. Cerebellum Ataxias. 2015;2:14.OpenUrl 34.↵Jones AL, Flanagan EP, Pittock SJ, et al. Responses to and outcomes of treatment of autoimmune cerebellar ataxia in adults. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(11):1304-1312.OpenUrl 35.↵Daif A, Lukas RV, Issa NP, et al. Antiglutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65) antibody-associated epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;80:331-336.OpenUrl 36.↵Malter MP, Frisch C, Zeitler H, et al. Treatment of immune-mediated temporal lobe epilepsy with GAD antibodies. Seizure. 2015;30:57-63.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed

|

Scooped by

Nesrin Shaheen

onto AntiNMDA |

No comment yet.

Sign up to comment

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...