An analysis of 500 hacking incidents across a wide range of industries has revealed trends that characterize a maturity in the way hacking groups operate today.

Researchers at Kaspersky have focused on the Russian cybercrime underground, which is currently one of the most prolific ecosystems, but many elements in their findings are common denominators for all hackers groups worldwide.

Pursuing new avenues

One key finding of the study is that the level of security on office software, web services, email platforms, etc., is getting better.

As Kaspersky explains, browser vulnerabilities have reduced in numbers, and websites are not as easy to compromise and use as infection vectors today.

This has resulted in making web infections too difficult to pursue for non-sophisticated threat groups.

The case is similar with vulnerabilities, which are fewer and more expensive to discover.

Instead, hacking groups are waiting for a PoC or patch to be released, and then use that information to create their own exploits.

Becoming more efficient

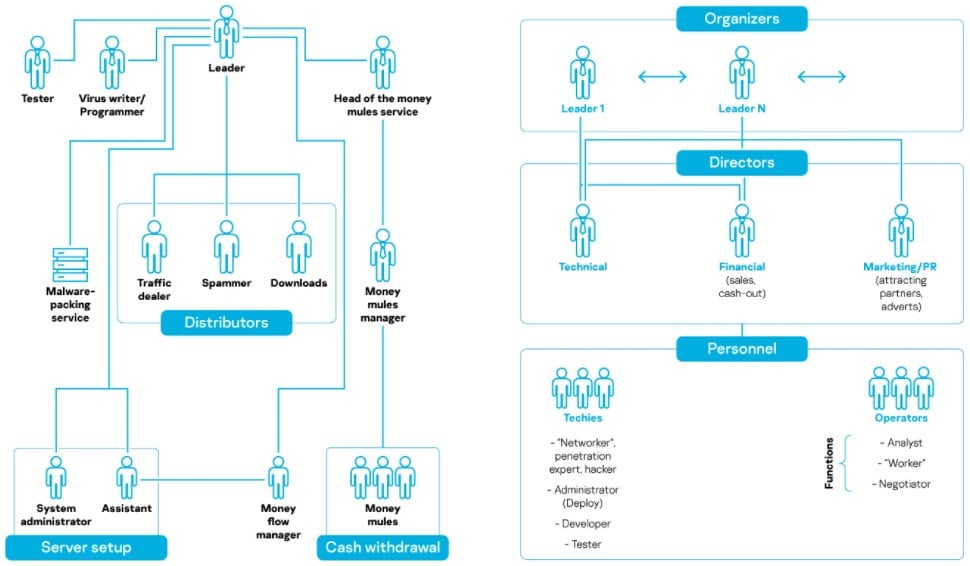

Hacking groups are now optimizing its member structure and providing distinct functional roles to each person.

In modern cybercrime operations, there’s no longer a need for malware authors and testers, because actors are sourcing their tools from central selling points on the dark web.

Moreover, with much of stolen money being transacted in cryptocurrency, actors only need money mules or someone to manage cash withdrawal operations when cashing out into fiat currency.

The same goes for account credentials, webshell access to various organizations, and even DDoS attacks. All of these are bought from providers instead of “employing” an expert in the team.

Source: Kaspersky

Another way of optimization for cybercriminals today is to turn to cloud service providers instead of choosing the more costly and risky option of renting or setting up their own physical server infrastructure.

The downside of this is that cloud servers are regulated and service providers are responsive to reports, but threat actors can always hop to other platforms or create new accounts when they’re uncovered.

One of the most striking differences that we see today compared to cybercrime practices from five years ago, is that large banks are no longer vigorously targeted.

Instead, hackers realized that it would be far easier and oftentimes more profitable to target companies with ransomware, RATs, and stealers, diverting payments through BEC attacks or forcing victims to pay a ransom.

“Back in 2016, our primary focus was on big cybergangs that targeted financial institutions, especially banks,” said Ruslan Sabitov, a security expert at Kaspersky.

“These days, the industries attacked are not limited to financial institutions and major attacks such as the ones we investigated in the past are thankfully no longer possible. Yet we can hardly say there is less cybercrime out there. Last year the total number of incidents we investigated was around 200. This year hasn’t concluded yet, but the count is already around 300 and keeps going.”

As the attacks increase in number, actor groups become more volatile and prone to disbanding, as collaborations are now limited to financial gains and not much else.

Finally, as members scatter and re-mix, so do their methods, and with more groups using the similar toolsets, the separating lines that helped identify each actor has become blurry.

Post a Comment Community Rules

You need to login in order to post a comment

Not a member yet? Register Now