-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Adam E. Barry, Austin M. Bates, Olufunto Olusanya, Cystal E. Vinal, Emily Martin, Janiene E. Peoples, Zachary A. Jackson, Shanaisa A. Billinger, Aishatu Yusuf, Daunte A. Cauley, Javier R. Montano, Alcohol Marketing on Twitter and Instagram: Evidence of Directly Advertising to Youth/Adolescents, Alcohol and Alcoholism, Volume 51, Issue 4, July/August 2016, Pages 487–492, https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv128

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Assess whether alcohol companies restrict youth/adolescent access, interaction, and exposure to their marketing on Twitter and Instagram.

Employed five fictitious male and female Twitter (n = 10) and Instagram (n = 10) user profiles aged 13, 15, 17, 19 and/or 21. Using cellular smartphones, we determined whether profiles could (a) interact with advertising content—e.g. retweet, view video or picture content, comment, share URL; and/or (b) follow and directly receive advertising material updates from the official Instagram and Twitter pages of 22 alcohol brands for 30 days.

All user profiles could fully access, view, and interact with alcohol industry content posted on Instagram and Twitter. Twitter's age-gate, which restricts access for those under 21, successfully prevented underage profiles from following and subsequently receiving promotional material/updates. The two 21+ profiles collectively received 1836 alcohol-related tweets within 30 days. All Instagram profiles, however, were able to follow all alcohol brand pages and received an average of 362 advertisements within 30 days. The quantity of promotional updates increased throughout the week, reaching their peak on Thursday and Friday. Representatives/controllers of alcohol brand Instagram pages would respond directly to our underage user's comments.

The alcohol industry is in violation of their proposed self-regulation guidelines for digital marketing communications on Instagram. While Twitter's age-gate effectively blocked direct to phone updates, unhindered access to post was possible. Everyday our fictitious profiles, even those as young as 13, were bombarded with alcohol industry messages and promotional material directly to their smartphones.

INTRODUCTION

Longitudinal research consistently documents exposure to alcohol advertising as an influential factor on whether youth will initiate alcohol use, and the quantity they will consume if they already drink (Ellickson et al., 2005; Anderson et al., 2009; Smith and Foscroft, 2009). Moreover, there appears to be a dose response–relationship between alcohol consumption and exposure to media and commercial communications, such that as exposure to alcohol advertising increases so too does the frequency of a drinker's consumption, as well as the odds of alcohol initiation (Snyder et al., 2006; Anderson et al., 2009). In addition to simply considering overall exposure to media, it has been proposed that it is equally important to consider and assess how associated messages are perceived and interpreted (Austin et al., 2006). When perceived as likeable, alcohol advertisements effectively influence an adolescent's intention to purchase the brand and products promoted (Chen et al., 2005). Positive intentions and expectations of underage persons to drink alcohol are predicted by their attitudes and perceptions of promotional messages, which alcohol advertising effectively influences (Fleming et al., 2004). Expectancies of underage persons have been found to be not only influenced by logic, but also affect, such that individuals progressively internalize message and subsequently employ them in their eventual decisions and also emulate the portrayals observed (Austin et al., 2006). In other words, receptivity to advertising has been proposed to be a continuous iterative process in which youth go through cycles of exposure, internalization, and incorporation into their identity (McClure et al., 2013). In sum, ‘alcohol ad exposure and the affective reaction to those ads influence some youth to drink more and experience drinking-related problems later in adolescence’ (Grenard et al., 2013, p. e369).

Self-regulation and youth exposure to alcohol advertising

Despite self-imposed regulations which call for limiting exposure of youth to alcohol advertising content and messages, there is evidence that the alcohol industry purposefully targets those under the minimum legal drinking age (MLDA; 18–20) (Ross et al., 2014). For instance, beer and liquor advertising appear more frequently in magazines with higher adolescent readerships (Garfield et al., 2003; King et al., 2009). Additionally, placement of television advertising appears during television programs with higher percentages of youth viewers than is allowable under alcohol industry voluntary regulations (CDC, 2013). Although alcohol brand websites require visitors to enter a birthdate—a content restriction practice known as an ‘age gate’—persons under the age of 21 represent large percentages (upwards of 50–60% for some brands) of the total in-depth visits to alcohol websites (CAMY, 2004).

With the proliferation of internet and social media, the alcohol industry has considerably decreased its advertising expenditures in traditional media outlets (e.g. television, radio, magazine) while at the same time substantially increased expenditures for digital and online outlets (FTC, 2014). This is concerning when you couple the alcohol industry's track record of advertising to youth with the fact that youth account for a large percentage of internet and social media adopters and users (Pew Research Center, n.d.). Approximately 95% of teenagers (12–17 years) use the internet (Pew Research Center, n.d.). Of these internet users, 81% engage with social media sites, the most popular of which include Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (Pew Research Center, n.d.). As Casswell (2004) contends, new developments in alcohol marketing are most likely to impact adolescents and young adults, as they are more likely to adopt new technology.

With regard to self-regulation, the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS) developed the Guidance Note on Responsible Digital Marketing Communications (2011), which asserts: It should be noted that DISCUS is a trade association which represents the leading producers and marketers of distilled spirits in the USA.

Digital marketing communications are intended for adults of legal purchase age.

Digital marketing communications should be placed only in media where at least 71.6% of the audience is reasonably expected to be of the legal purchase age.

Digital marketing communications on a site or web page controlled by the brand advertiser that involve direct interaction with a user should require age affirmation by the user prior to full user engagement of that communication to determine that the user is of legal purchase age.

Current investigation

Considering (a) youth and adolescents are highly engaged with social media applications such as Twitter and Instagram, (b) alcohol advertisers are expanding their social media presence and (c) advertiser practices have targeted youth and adolescents across more traditional media platforms, it is essential to examine whether youth are able to interact with and/or be advertised to on social media platforms. The current investigation employed fictitious social media profiles between the ages of 13–21 in order to assess whether alcohol companies are adhering to the recommendations outlined in the DISCUS's Guidance Note on Responsible Digital Marketing Communications (2011) in their marketing practices on the social media platforms of Twitter and Instagram. Twitter and Instagram were specifically chosen for several reasons. First, the FTC (2014) contends that Facebook effectively restricts access to alcohol industry pages to those over the minimum legal drinking age, and that alcohol advertisements cannot be placed on the pages of persons who are younger than 21. Thus, existing data on Facebook practices eliminated it from consideration. Second, following Facebook, Twitter and Instagram are the most popular social media sites among youth between the ages of 12–17 (Pew Research Center, n.d.). Specifically, we examined whether youth could (a) view and interact with online social media alcohol advertising on Twitter and Instagram, and (b) follow and subsequently receive promotional materials/messages from alcohol brand profiles on Twitter and Instagram. Based on previous investigations into the efficacy of age gate technology employed on the social media site YouTube (Barry et al., 2015), we hypothesized that youth would have access to, and be able to follow, all alcohol advertising materials/promotions.

METHODS

Creation of user profiles

We created five fictitious male and five fictitious female Twitter (n = 10) and Instagram (n = 10) user profiles, which were each assigned an age of 13, 15, 17, 19 and 21. For each social media platform there was a male and female profile for each age category. We specifically chose to have profiles begin at age 13 since nearly half of American 8th graders (44%) have tried alcohol (Johnston et al., 2005). Additionally, these age ranges were selected because they correspond with several different phases of life: middle-school (age 13), high school (ages 15 and 17), and college (ages 19 and 21). The profiles were assigned first and last names randomly selected from the 20 most popular names on the 2010 United States Census. Each fictitious profile was used to interact with both the Twitter and an Instagram social media channels which produced usage and engagement metrics. These metrics were assessed solely via mobile smartphone devices. Thus, it is possible user experiences would be different from those using a desktop/laptop/tablet computer. The only information that was entered during setup of the accounts on Twitter and Instagram was user name, age, and sex.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data obtained from Twitter and Instagram provided information on the ability of youth to access, view, interact (e.g. re-tweet, ‘like’) and follow official alcohol brand pages. In order to identify what alcohol companies to examine, we selected the 25 alcohol brands that are most popular/consumed (i.e. highest prevalence of use within the past 30-days) by adolescents in the USA (see Siegel et al., 2013). Brands were excluded if we were unable to identify their official Twitter and Instagram account. Of these 25 brands, only 22 had official pages on both Twitter and Instagram.

Assessment

Data was collected in two phases using Twitter and Instagram mobile applications. Phase 1 focused on analyzing access and interaction. Specifically, for each of the 22 brands, all fictitious profiles attempted to view the official page of each alcohol brand. Next, users attempted to interact with the official page. Interaction was judged to occur if a profile could (a) retweet, (b) view video content, (c) view picture content, (d) like, (e) comment, (f) share URL, and/or (g) share content (e.g. retweet, regram). Phase 2 of data collection focused on whether our fictitious youth profiles could follow and receive direct updates from each of the 22 alcohol brands. Updates were considered any distinct post consisting of either a video, picture, or text. Updates were not classified by type; instead, each new post received was counted as an update. Each fictitious profile recorded data from both Twitter and Instagram for a period of 30 days. Phase 2 focused on the frequency with which an alcohol company sent updates (e.g. video, picture or text-based sentences) to our fictitious profiles. It is important to note that for each phase of data collection, all profiles entered their assigned fictitious birthdate when prompted. The Institutional Review Board determined this research to be exempt from review.

RESULTS

Phase 1 findings

All user profiles, both those under the MLDA of 21 and those of legal drinking age, were able to view, interact, and comment on advertising content from the alcohol companies on both Instagram and Twitter. In other words, all profiles, regardless of age (13–21), could fully interact with Instagram and Twitter content, such as view videos, comment on pictures, forward advertisements to others, like and retweet posts from alcohol industry feeds/pages. Table 1 presents a general overview of findings from Phase 1.

Ability of users (aged 13–21) to view and interact with official pages of 22 alcoholic brands on Twitter and Instagram

| Age . | Gender . | Follow official page . | View page . | View video and picture content . | Retweet . | Embed to social media . | Share URL . | Comment or like . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Instagram . | ||

| 13 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 13 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 19 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 19 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 21 | Male | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 21 | Female | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Age . | Gender . | Follow official page . | View page . | View video and picture content . | Retweet . | Embed to social media . | Share URL . | Comment or like . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Instagram . | ||

| 13 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 13 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 19 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 19 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 21 | Male | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 21 | Female | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Ability of users (aged 13–21) to view and interact with official pages of 22 alcoholic brands on Twitter and Instagram

| Age . | Gender . | Follow official page . | View page . | View video and picture content . | Retweet . | Embed to social media . | Share URL . | Comment or like . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Instagram . | ||

| 13 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 13 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 19 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 19 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 21 | Male | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 21 | Female | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Age . | Gender . | Follow official page . | View page . | View video and picture content . | Retweet . | Embed to social media . | Share URL . | Comment or like . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Twitter . | Instagram . | Instagram . | ||

| 13 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 13 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 19 | Male | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 19 | Female | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 21 | Male | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 21 | Female | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Phase 2 findings

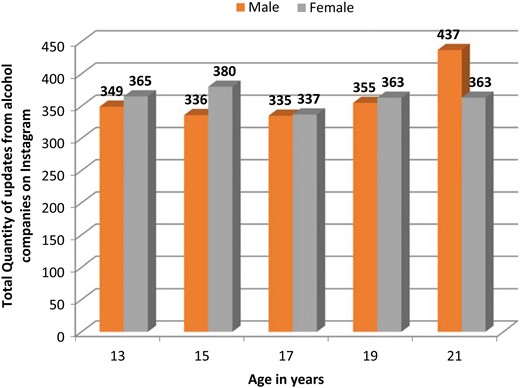

As you will note from Table 1, Twitter's age-gate only prevented underage profiles from following each of the official alcohol company pages, and subsequently from receiving direct updates/promotional advertising. However, this feature was not employed on Instagram; thus, all profiles (13–21) on Instagram could receive alcohol industry advertisements directly to their smartphones. Figure 1 outlines the cumulative number of Instagram updates received by all profile users over a period of 30 days (total n = 3620). On average, each user received 362 Instagram updates directly to their smartphone within a month. Given Twitter's age gate preventing under-age profile users from following and receiving updates from alcohol companies, only our two legal drinking age profiles received direct to consumer promotional material (total n = 1836) via their Twitter account during the 30 days of data collection (male n = 917; female n = 919).

Cumulative number of Instagram updates sent from 22 alcohol companies to users (13–21) over a 30-day period.

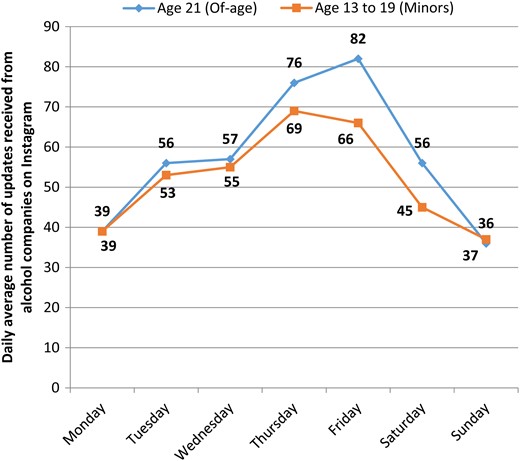

On average, all Instagram profiles received 12–13 updates from alcohol companies each day (approximately 91 per week), regardless of age. Figure 2 outlines the average number of Instagram updates sent to of-age and underage profiles as a function of day of the week. Frequency of alcohol advertising updates increased as the week progressed, reaching its peak on Thursday and Friday.

Comparison of average weekday Instagram updates received by of-age profiles and underage profiles within 30-day period.

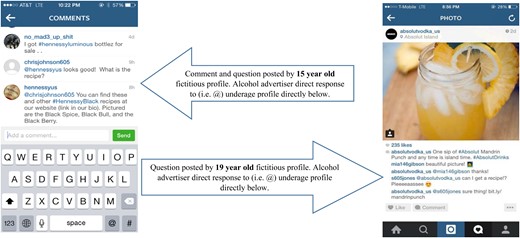

Fortuitous findings

In the process of evaluating the main hypothesis proposed in this study, there were noteworthy exploratory findings that were not considered a priori. As noted above in Phase 1, to fully determine the level of access that our profiles had to alcohol industry pages we sought to see if it was possible to view and interact with (e.g. like, comment, share) promotional material. As a result of this interaction we learned that entities who maintained and controlled the alcohol brand pages would directly interact/correspond with our underage profiles. As noted in Fig. 3, the representative/controller of alcohol brand Instagram accounts would respond directly to our underage profiles. Secondly, alcohol advertisers, representatives, and/or enthusiasts ‘followed’ our underage profiles. Each of the underage profiles included in this investigation received follow notifications from separate, distinct, and uninitiated alcohol advertisers, representatives, and/or enthusiasts that were not part of our sample of 22 alcohol brands.

Examples of alcohol industry direct communication/correspondence with underage profiles.

DISCUSSION

While there exists a plethora of scholarly investigations which have examined the impact of alcohol advertising transmitted through traditional mediums (i.e. television, radio, newspapers), there is much less peer-reviewed literature which examines alcohol advertising on emerging social media platforms. To date, we are aware of only two studies (see Winpenney et al., 2014; Barry et al., 2015) that have attempted to examine the accessibility of alcohol content to underage persons via social media. Unlike these previous studies, however, this investigation examined Instagram and Twitter in lieu of Facebook and YouTube. Overall, our findings point to the unobstructed accessibility youth have to alcohol advertising and promotion via both Instagram and Twitter. In other words, there was no restriction to viewing and interacting with the content posted on alcohol brand pages. Moreover, in the case of Instagram, age-gate technology did not restrict underage profiles from receiving updates directly to their smartphones. These findings echo Nicholls’ (2012) contention of ‘everyday, everywhere’, such that everyday our fictitious profiles, even those as young as 13, were bombarded with messages and post directly to their personal smartphones.

As alcohol companies are cutting down on traditional advertising, they appear to be increasing their efforts towards online or digital advertising (FTC, 2014). This is concerning for several reasons. First, youth and adolescents represent a large percentage of internet and technology users (Pew Research Center, n.d.), which would disproportionately expose them to digital alcohol advertisements above and beyond of-age drinkers. Second, the self-imposed regulations established by the alcohol industry have failed to protect and/or limit youth from exposure to their advertising content via traditional mediums (Anderson, 2009; Tanski et al., 2015). In fact, due to the relative ineffectiveness of the industry's self-regulation, public health researchers and government officials in some countries are considering implementing a ban on alcohol advertising (see Jernigan, 2013; Parry et al., 2014). Others have called for imposing a levy on alcohol advertising in order to establish a fund which can be used to develop counter-advertising messages (see Harper and Mooney, 2010). Third, previous research has found systemic code violations with regard to the content depicted in alcohol industry advertising (Vendrame et al., 2010; Babor et al., 2013), as well as the content on their respective websites (Gordon, 2011). While this investigation focused exclusively on access, interaction, and exposure to alcohol advertising on social media, our findings highlights the need for future research examining the content of the messages sent to underage consumers on social media. In an examination of the marketing content posted on 12 of the leading UK alcohol brand Facebook pages, Nicholls (2012) documented the use of interactive games, links to product advertisements encouraging viewers to suggest alternative endings to their commercials, as well as messages encouraging drinking—regardless of the day of the week. To date, however, examinations of the content on social networking platforms such as Twitter and Instagram are unavailable.

The current investigation highlights the alcohol industry's use of social media platforms to send direct to consumer advertisements regardless of age. In other words, the industry has violated their own marketing code restrictions and ultimately failed to restrict access and exposure of underage persons to their advertising content. Moreover, representatives/controllers of their alcohol brand pages are actually communicating directly with persons under the MLDA. We did not, however, measure level of interaction among each of our respective profiles and the alcohol brand pages. Instead, to address our initial research question, we sought to simply determine whether profiles could view and interact with alcohol brand pages. The lack of a measure of interaction for each of our profiles (i.e. how many times each profile liked a post, posted a comment) prohibits us from determining whether involvement resulted in differing quantities and frequencies of updates directly received. Future research, therefore, should seek to determine whether differing levels of engagement and interaction among social media users results in altered levels of exposure to alcohol industry promotions.

The findings reported herein highlight not only an American public health issue, but an international health concern given the borderless reach of digital media. In fact, in their Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol the World Health Organization called for a reduction in the number of youth exposed to alcohol advertising (WHO, 2010). Given that alcohol advertising is one of the factors influencing the beliefs and behaviors of young people, and contributing to their decision to consume alcohol despite being below the MLDA (Grube, 2004), our findings demonstrating the ineffectiveness of age-gate technology should serve as a call for (a) greater political advocacy from public health officials and researchers, and (b) additional research examining how emerging social media technologies are being leveraged by the alcohol industry in the marketing of their products.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest (financial or otherwise) to report.

REFERENCES