Not so rare - Autoimmune encephalitis is as common as infectious encephalitis

Once considered a rare disease class, new findings suggest that autoimmune encephalitis (AE) is much more common than previously thought. AE is a class of diseases whereby host antibodies inappropriately target host brain proteins leading to inflammation and/or target protein dysfunction. In the case of the most common form of AE, anti-NMDA encephalitis (NMDA-AE), patients develop a range of psychiatric symptoms that are nearly indistinguishable from schizophrenia and other psychotic-spectrum disorders: delusions, hallucinations, and bizarre behavior. Ultimately these individuals progress to seizures and cardiopulmonary instability but the psychiatric features of NMDA-AE so closely mirror those of psychotic disorders that it has led some in our field (including me) to ask whether these or similar antibodies may play a role in idiopathic psychosis.

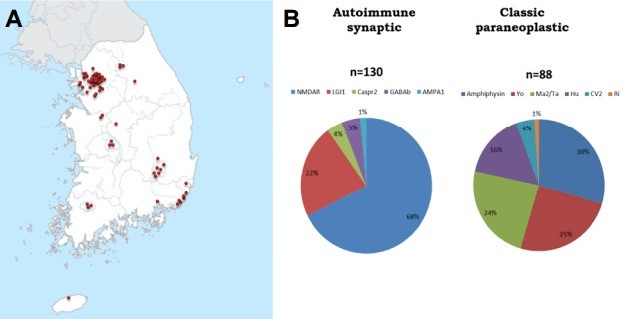

In 2012 the California Encephalitis Project examined 761 undiagnosed cases of encephalitis and found that NMDA-AE was significantly more common than viral encephalitis, about four times more common. This finding has been effectively replicated in a distinct encephalitis cohort by a group out of the Mayo Clinic who found that, as a disease class, AE is nominally more common than viral encephalitis (although statistically they are equally common). As such, in two distinct geographic regions in the United States, AE has been found to be just as or more common that viral encephalitis. Even outside the US AE is also proving to be a disease entity worth knowing about. A group out of Korea found that out of 2500 encephalitis cases evaluated between 2012 and 2015, 8.6% had known AE autoantibodies. It's no wonder that more and more, physicians are familiarizing themselves with the unique features of various AE disorders.

Against this backdrop of increasing awareness in the medical community, the international psychiatry is beginning to take a hard look at whether the autoantibodies implicated in classical AE might also drive mental illness via an attenuated form of encephalitis. Immune dysregulation in mental illness has been well-documented and some suspect that brain-targeting autoantibodies may be a component of the broader immune dysfunction observed across a range of in psychiatric illnesses. Pioneering researchers out of the UK have launched a pair of clinical studies looking to address the role of AE antibodies in first episode psychosis.

The implications of autoantibody-mediated mental illness would be significant, in part because we haven't had a new class of pharmacologic agents for the treatment of psychosis since the 1950's (or 1970's if you consider atypical antipsychotics a novel class). Although there are case reports of immunotherapy coinciding with remission of psychiatric symptoms, definitively implicating a specific autoantibody in an individual's psychiatric disease will prove challenging. While our neurology colleagues are known for their careful delineation of well-circumscribed clinical phenomena, imaging, and functional measurements, psychiatric phenomena are not so discrete nor do they typically lend themselves to neuroimaging. As a result, it will be difficult to demonstrate that a single autoantibody explains a pattern of psychiatric symptoms and behaviors in a single patient. Just as in the genetics of psychiatry, the name of the game for autoantibody research will be getting sufficient numbers to make a strong and replicable associations.

Despite the challenges, there is sufficient reason to believe that autoantibodies play a role in some (small) portion of individuals with idiopathic mental illness and that this area of research is worth pursuing. Over the course of a series of posts I hope to address some of the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead by taking a critical look at the existing literature, highlighting unanswered questions, and suggesting strategies that may help clarify the role of autoantibodies in the pathogenesis or perpetuation of psychiatric disease. We've got a long road ahead of us. Next up, a close look at anti-NMDA antibodies in psychiatric disease.

I welcome comments and corrections.

-- CMB

Founder, The Rocha Health Center for Men and Peak Performance. Men's Health through a Functional medicine lens.

4yChris, great article. I saw you’re in / were in an immunopsychiatry fellowship and I think that’s exciting...that there is such a fellowship. I’m afraid that too little of what is known from cutting edge research is applied in a clinical setting (atleast in conventional primary care settings). The effect the gut-immune axis has on the brain, and subsequently on psychiatric conditions is immense and unfortunately not talked about enough. Would love to hear about other things your working on. Cheers, Gabe

E-Learning Consultant and Contractor

6yHi Christopher, I was also very interested in the idea of no inflammation being caused? Though I also wonder if antibody is the correct term? As it isn't attacking the protein, but rather altering its function?

Biotech Professional and eater of good bread.

6yHi Christopher, this is a very interesting topic. I have worked on characterising antibodies from post rheumatic fever blood samples (sydenham chorea, and supposed PANDAS). I just wanted to point out that some of the antibodies I worked on were not likely triggering inflammation or encephalitis. For example, one of the mAb's isolated from a Sydenham's sample bound dopamine receptor D1 and enhanced the effect of dopamine by about 50 fold. Something to keep in mind if you decide to pursue this field. Best regards, Jon